Censorship Watch

Dem Operatives Exposed for Russian-Style Facebook Tactics in Alabama Senate Race

Most of the fake news is still yammering about Russian deception, but Alabama Democrats (presumably, non-bot Americans) are running the most deceptive campaign of all.

It’s so blatantly misleading, even the failing New York Times had to cover it!

Posing as Prohibitionists, 2nd Effort Used Online Fakery in Alabama Race

By Scott Shane and Alan Blinder

Jan. 7, 2019

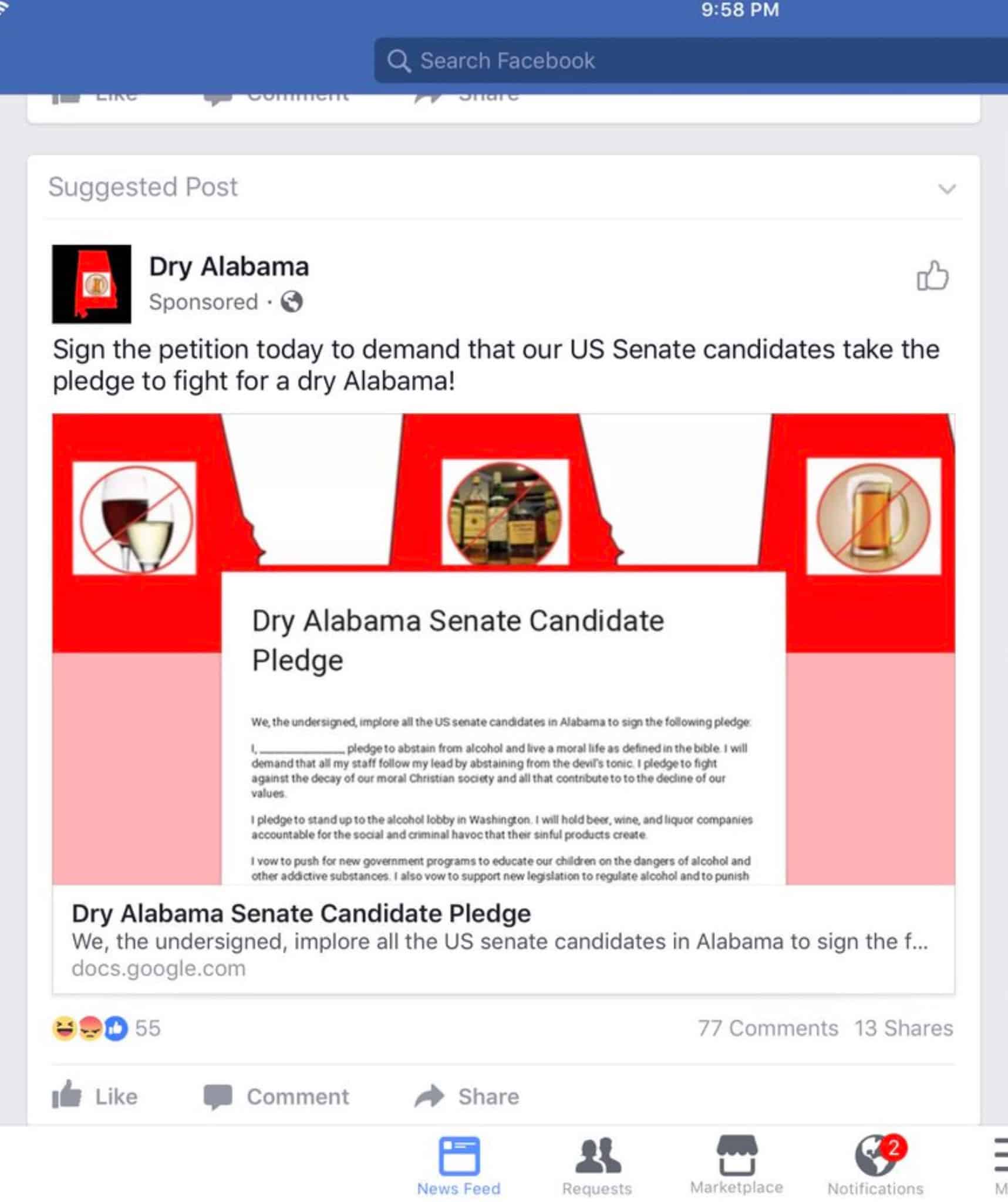

The “Dry Alabama” Facebook page, illustrated with stark images of car wrecks and videos of families ruined by drink, had a blunt message: Alcohol is the devil’s work, and the state should ban it entirely.

Along with a companion Twitter feed, the Facebook page appeared to be the work of Baptist teetotalers who supported the Republican, Roy S. Moore, in the 2017 Alabama Senate race. “Pray for Roy Moore,” one tweet exhorted.

In fact, the Dry Alabama campaign, not previously reported, was the stealth creation of progressive Democrats who were out to defeat Mr. Moore — the second such secret effort to be unmasked. In a political bank shot made in the last two weeks of the campaign, they thought associating Mr. Moore with calls for a statewide alcohol ban would hurt him with moderate, business-oriented Republicans and assist the Democrat, Doug Jones, who won the special election by a hair-thin margin.

Matt Osborne, a veteran progressive activist who worked on the project, said he hoped that such deceptive tactics would someday be banned from American politics. But in the meantime, he said, he believes that Republicans are using such trickery and that Democrats cannot unilaterally give it up.

“If you don’t do it, you’re fighting with one hand tied behind your back,” said Mr. Osborne, a writer and consultant who lives outside Florence, Ala. “You have a moral imperative to do this — to do whatever it takes.”

The discovery of Dry Alabama, the second so-called false flag operation by Democrats in the fiercely contested Alabama race, underscores how dirty tricks on social media are creeping into American politics. The New York Times reported last month on a separate project that used its own bogus conservative Facebook page and sent a horde of Russian-looking Twitter accounts to follow Mr. Moore’s to make it appear as if he enjoyed Russian support.

The revelations about the first project, run in part by a cybersecurity company called New Knowledge, led Facebook to shut down five accounts that it said had violated its rules, and prompted Senator Jones to call for a federal investigation. There is no evidence that Mr. Jones encouraged or knew of either of the deceptive social media projects. His spokeswoman, Heather Fluit, said his legal advisers were preparing to file a formal complaint with the Federal Election Commission.

Both Alabama projects were devised shortly after the exposure of the full dimensions of Russia’s fraudulent use of social media in the 2016 presidential race, when thousands of Facebook and Twitter accounts posed as Americans. Because the Russian operation attacked Hillary Clinton and helped Donald J. Trump, Democrats have spoken out most vehemently against it.

So some Democrats were discomfited by the revelation that the first of the Alabama efforts was explicitly devised to try out the tactics of the Russian operation, according to an internal report on the project obtained by The Times. Rather than Russians working in St. Petersburg posing as Americans, this time Democrats — most of them far from Alabama — pretended to be conservative state residents.

The first of the Alabama efforts was funded by Reid Hoffman, the billionaire co-founder of LinkedIn, who apologized and said he had been unaware of the project and did not approve of the underhanded methods. The second was funded by two Virginia donors who wanted to defeat Mr. Moore — a former judge accused of pursuing sexual relationships with underage girls — according to a participant who would speak about the secret project only on the condition of anonymity and who declined to name the funders.

The two projects each received $100,000, funneled in both cases through the same organization: Investing in Us, which finances political operations in support of progressive causes. Dmitri Mehlhorn, the group’s managing partner, declined to comment on whether he approved of the tactics he had helped pay for. But after the Times report in December, he acknowledged, in a post on the online forum Medium, a “concern that our tactics might cause us to become like those we are fighting.” He declared that “some tactics are beyond the pale.”

Another organizer of the project, according to two participants, was Evan Coren, a progressive activist who works for the National Archives unit that handles classified documents. He did not respond to requests for comment. Beth Becker, a social media trainer and consultant in Washington who handled Facebook ad spending for the Dry Alabama page and the project’s other Facebook page, called Southern Caller, said in an interview that a nondisclosure agreement prohibited her from saying much about the project.

But, she added, “I don’t think anything this group did crossed any lines.”

That may be true in the sense that neither law nor regulations set any clear limits on social media activity in elections. “The law has clearly not caught up with social media,” Ms. Becker said.

But there is no doubt that the progressive Democrats who created the now-defunct Facebook pages — and the related Twitter feeds, seeming afterthoughts with negligible reach — were trying to deceive voters about their identities and real views. “Re-enact Prohibition and make Alabama dry again!” said one post. “Democrats continue to put party before country,” said another.

Facebook’s community standards, which were tightened in 2018, emphasize “authenticity” and prohibit “misrepresentation,” including coordinated efforts to “mislead people about the origin of content.”

Political social media trickery of this sort is usually well hidden and hard to detect without help from an insider, so it’s difficult to say how common it has become. Some political veterans warn that without new laws or regulations explicitly outlawing fraudulent social media tactics, both parties may feel pressure to use them simply to stay competitive.

There were at least two more social media operations intended to help Mr. Jones’s campaign, run by small companies called Tovo Labs and Dialectica. Neither responded to queries about their tactics. A public account by Tovo Labs of its effort described setting up websites for Christian conservatives and moderate conservatives but claimed all the content was “legitimate material” and its methods “ethical.” A pitch to potential customers from Dialectica offers “a new generation of information weapons” to battle “fake news,” and a marketing email shared with The Times says the company worked in the Alabama race’s “meme war” for at least three months.

Mr. Osborne, who said he helped conceive the Dry Alabama project and wrote for the Southern Caller page, said the effort began in conversations with acquaintances from his years at the annual Netroots Nation progressive gatherings. They discussed what tactics might help Mr. Jones’s chances and zeroed in on tensions within the Republican Party over whether drinking should be permitted in Alabama, where the number of dry counties had dwindled.

“Business conservatives favor wet; culture-war conservatives favor dry,” he said. “That gave us an idea.”

Essentially, the aim was to frighten the business conservatives — who could be targeted with ads using Facebook’s tools — with the potential implications of a Moore victory. Some ideas were nixed by organizers: A raffle of an AR-15 assault rifle was out, Mr. Osborne was told, as was outright homophobic language.

“I learned that if you’re doing a false-flag conservative page for a liberal donor, there are limits,” he said. But he said he enjoyed mimicking the voices of his conservative opponents who dominate in the state.

By the time the project got funding, there were only two weeks left in the race. With salaries needed only briefly, about 80 percent of the $100,000 went toward Facebook ads.

Elizabeth BeShears, a Republican communications consultant from Birmingham, was amused when she spotted a Dry Alabama ad on Facebook demanding that candidates pledge to try to ban drinking, because her husband’s family had strongly supported a recent effort to turn a county “wet.”

She assumed the Dry Alabama ads were aimed at anti-alcohol conservatives, and posted on Twitter a screenshot of the Facebook ad with the remark, “Y’all’s targeting is so wrong.” In fact, Mr. Osborne said, Ms. BeShears was the perfect target for the ads. She voted for Mr. Jones out of disgust for Mr. Moore, though she didn’t need the Dry Alabama ad to persuade her, she said.

Mr. Osborne said the stats he was given on the reach of the brief Facebook operation were impressive: 4.6 million views of the Facebook posts, and 97,000 engagements — for instance, “liking” or sharing posts. Simple videos pushing the Dry Alabama message were watched 430,000 times, he said.

Given Mr. Jones’s slender margin of victory — about 22,000 votes, out of more than 1.3 million — it is hard to say for sure that Dry Alabama had no impact. But many other independent efforts were at play on both sides, and the amount spent on the two false flag projects was relatively tiny in a race that cost at least $51 million, including the primaries.

Ms. BeShears said she doubted the Dry Alabama effort had had a significant effect on the outcome, in part because Mr. Moore was seen as a toxic candidate and Alabamians had long harbored strong views about him. By the time the project was carried out, few voters were undecided, she said.

“I don’t think most people saw it and thought that’s a reason to vote or not to vote for Roy Moore,” she said. “The only people who were still hanging on to the Roy Moore bandwagon were going to be there no matter what. Whether you’re still going to be able to drink a beer at your tailgate was not going to sway them.”